Interview by Cristina Enescu

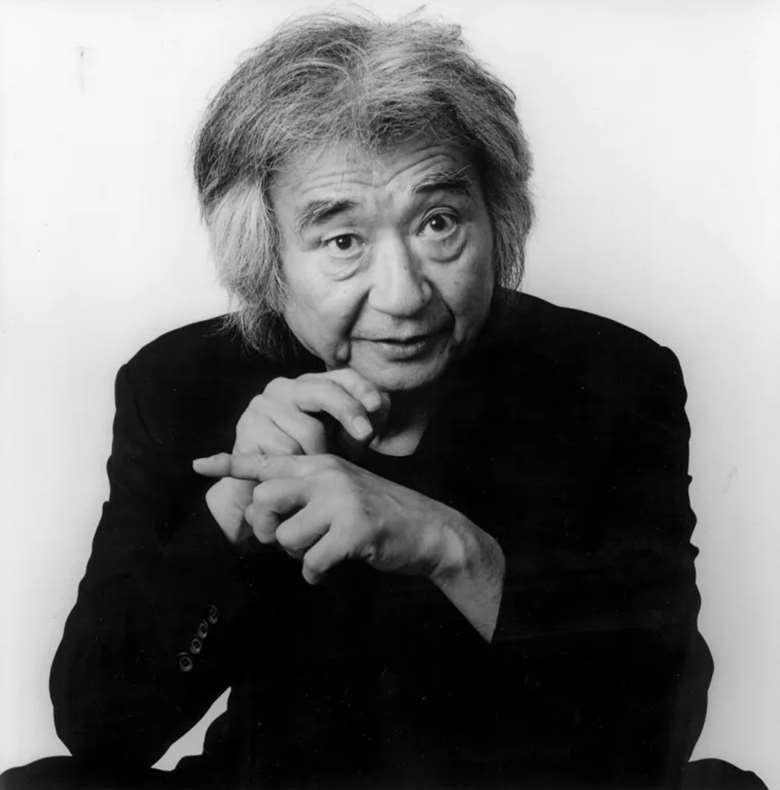

Nicola Campogrande is an accomplished Italian classical music composer whose works are frequently performed in important venues and festivals, also a music journalist, author, Artistic Director of the international MITO SettembreMusica Festival (happening simultaneously in Milan and Turin)– and, since 2012, a sort of musical painter. His first portrait, of a lady who shall remain anonymous, is „R – A portrait for piano and orchestra”, which was performed during the George Enescu Festival 2019.

Catching up with Nicola Campogrande in Bucharest, he shared the unusual and enticing story of how this work came to be, and also some thoughts on the interesting and evolving relationship between contemporary classical music and audiences.

„R – A portrait for piano and orchestra” is famous not just because of its music, but also the story behind it.

Indeed. One day, a stranger called and asked me to compose a musical portrait of his fiancé (the couple will remain anonymous, as I signed a nondisclosure agreement). At first, I thought he was crazy. I’m not a painter, I’m a composer. I said I’ll think about it. Some time later I visited an exhibition in a castle in Italy, with paintings featuring historic characters and also exhibits of a contemporary artist, where within old painting frames there were displays with videos of actors dressed like historical characters, who at times moved and talked. Seeing this I realized I could write a musical portrait by working with tempo and movement, depicting through music how that woman moved, how she placed herself in space and time, so describing her life rather than her appearance. That’s when I accepted the job.

During that same time two other things happened: the famous Russian pianist Lilya Zilberstein contacted me wanting to do some work together. Also, as if all the right stars would have gotten aligned perfectly, the Verdi Orchestra of Milan invited her to play in a concert with them, for which they needed an addition to the program, some new composition.

By that time, I hadn’t started to work on the musical portrait yet, but I was thinking about it. I met the gentleman over dinner, and he started to tell me highly personal, even intimate details about how they met, how their mature love had developed. It was very emotional but also rather embarrassing, as I didn’t know these people. He then sent me some pictures of her. For the next 9 months, just as my wife and I were expecting our third child, I lived surrounded by those pictures and I composed. When I was close to finishing, the gentleman invited me to a dinner with friends at their house to also meet his lady, but the project was supposed to still be a secret. It was strange… this woman who had already turned into music for me, whose eyes I was so familiar with from the pictures, was suddenly there next to me, talking, eating…

There is a part of this composition, called La Conquista (The Conquer), because she is a power lady, very active and dynamic in her family, her work, with sports. Then there’s a part called Notte (Night), quite erotic in fact, because the gentleman even told me lots of details about their nights together. I had already written these parts when I went to that dinner and I saw my muse walk and talk, and then that night I couldn’t sleep, I was quite bewildered.

A bit of a Pygmalion effect?

Perhaps that’s a good description…. Some months later, before the premiere with the Verdi Orchestra, the gentleman invited her to the general rehearsal. I was on stage with Lilya Zilberstein and the great Verdi Orchestra, and with the corner of the eye I was watching her. Her fiancé had made a book recounting the whole story, with the same pictures that I had been given of her. When he gave it to her from underneath her seat where it was hidden, and she grasped what was about to happen, she rushed crying on the stage and hugged me.

The night of the concert, sitting behind me was lady with her mother. When the orchestra got to play the third part of this composition, The Conquest, I overheard the mom turn to her daughter and say `I’ve always told you, you always do too many things at a time, you can hear that in the music as well`. I was so happy… The mother of the woman I had painted with my music had recognized her daughter in it. Thus, this composition got a life of its own.

Is there any precedent regarding a musical portrait of this sort in the history of music that you know of?

Not exactly, this is in fact what scared me. The closest thing I could find are the Enigma Variations by the English composer Sir Edward Elgar [an orchestral work including 14 variations on an theme, each one being a musical sketch of a friend of his]. Each variation bears the initials of a friend of his. But they’re not quite portraits, so it’s different.

How was your life as a composer after that project?

I make a living by composing commissioned works, and I’m very happy and proud to be able to do this. But I remember well that the piece I was commissioned to do after this `R – a portrait for piano and orchestra` left me feeling somehow disappointed, it didn’t have that sense of challenge and also of anticipation. After that I’ve paid even more attention to my works, and I kind of rather prefer writing music that is maybe less paid but strongly desired by the one who requests it.

More than a few are still reluctant regarding contemporary classical music. You went even beyond that. How do you think this work is perceived by audiences?

Composers have a huge responsibility regarding that part of the audience who still rejects contemporary music. For many decades I think there was a lot of terrible contemporary music composed, totally autoreferential. Composers didn’t enjoy the music they were writing. After let’s say 1930 or certainly after the Second World War and the Holocaust composers adopted a sort of ideological refusal of beauty, many felt they could not compose about beauty anymore, that through their works they needed to testify about the horrors of reality. This did make sense in the post-war years, but music had since forever been a vehicle for beauty, joy, intelligence, and then it had come to being a vehicle for nothing. So, it got to a point where people who went to concert halls were completely waterproof regarding that music, there was no relationship built with it. I guess the audience had at that point all the reasons to run away from contemporary music. But then things change. Nowadays there are dozens of composers worldwide who write exciting, rich, touching, sexy music, which people enjoy listening to.

You spoke previously about the power of music to create relationships. What kind of connections do you feel your music facilitates?

That’s a beautiful and also difficult question. I write music that I myself enjoy first of all, and also try to bring my small contribution to the world. Composers can be useful to the world to the extent in which they create energy, beauty. In time I’ve discovered that my music is quite empathetic towards musicians. They seem to enjoy it lots. Like after the concert at the Enescu Festival, when I went on stage for the applause, the musicians were applauding me just as strongly as the audience. That’s what I like, that from my life – an Italian who enjoys good food, has three children, reads, travels, rides the bike – I can create energies that spread to the musicians and the audience.

You are also a writer, and one of your books is interestingly called “Occhio alle orecchie. Come ascoltare musica classica e vivere felici”(“Eye to the ears. How to listen to classical music and live happily”). Was it written before or after the adventure with the musical portrait?

It was after.

That title speaks about exactly what you did with the `R` composition, putting the worlds of eyes and the ears together.

You’re right.. I hadn’t thought about that. I think that the way people listen to classical music in concert halls is changing, and rightfully so. Sometimes we need to stop and think about it. Including what the task of the composers and the interpreters is in the age of internet, when people have the choice of paying a ticket at a live concert or listening to music online.

Indeed, what is still the value of paying a ticket and going to a live concert?

Well first of all, the answer has to do with the essence of classical music, which is much more difficult to define than, let’s say, rock or pop music, because classical music has simultaneously a big strength (it’s been evolving throughout many centuries) and a big weakness, which is that it’s a music made of relationships – between notes, parts, people- which change continuously. If I write a tango, at the firsts beat I’ve already established what will happen later. That doesn’t happen in classical music, here the composer starts to work and then at some point finds himself bedazzled by what was born from the material he put into the composition.

Does this improvidence and lack of total control make classical music more delicate?

Yes, but then there’s also the performing. Every time classical music is being performed, it takes at times just one slight change in accent or dynamics and the direction of the interpretation of that piece will inevitably change. And that’s so beautiful! For that, I think it still makes a lot of sense to go to live concerts, every time it is a rebirth, in real time, of that music.

You said once that music is “a place of hospitality and exchange”. How would you translate that?

That means that people come together very naturally and make and listen to music together while using the same musical language, often without ever having met before. Here there was the work of an Italian composer, printed in Germany, performed in Romania featuring a Croatian pianist. Music is a form of expression where various people can both „talk” at the same time without annoying each other. We also listen together, in music. If politicians would also be musicians, we’d all be much better off, they would be able to listen to each other, find harmony and stimulate each other. Music is a beautiful paradigm. In an orchestra there are people with very different specialisations, they have studied in different places and manners, yet they all play together with synchronicity and harmony.

What treatment would you recommend for those still wary if not downright scared of classical music, often times more out of a prejudice than actual fear or trauma?

First, I’d drop the adjective `contemporary`. I am a classical music composer, that’s it. Mozart too was a “contemporary classical music composer” at his time. Then, there’s something I always do when making the repertoire for concerts: I combine contemporary pieces with ones from the past. That’s how it’s always been done until the 1900s. Creating enclosures or sanctuaries for living composers is not great. Artistic directors just need to become aware of how much new good music there is and have the curiosity and courage to discover it.

For those who haven’t tasted your music yet, which composition would you suggest they start with?

Well, “R – A portrait for piano and orchestra” would be a good one because it has this story behind it which can maybe also stimulate the imagination. You can find on Youtube the beautiful performance of Lilya Zilberstein. My invitation, though, remains mainly that people come to listen to live music performances. Those are the best.