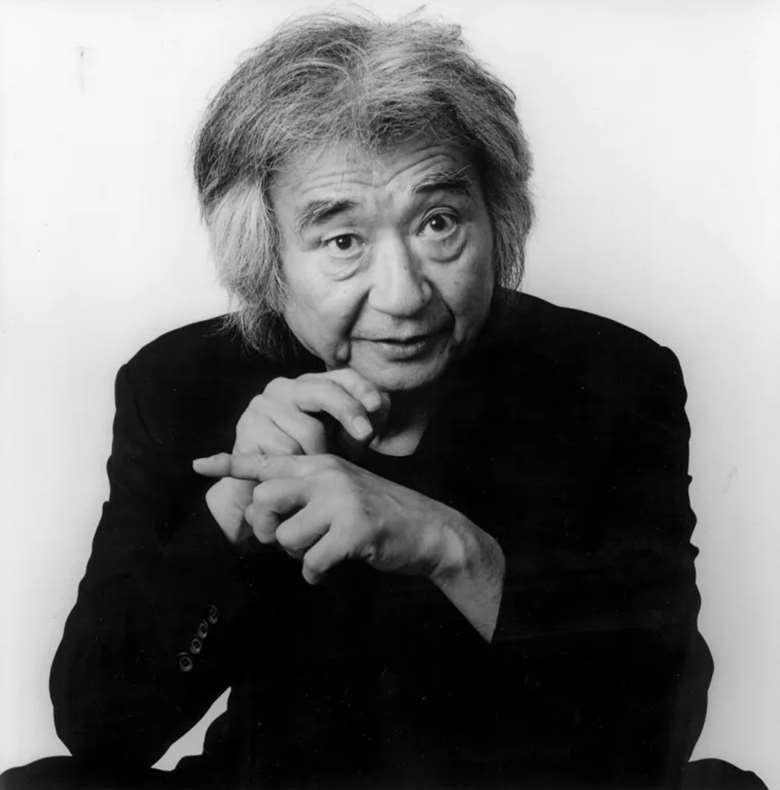

Interview by Cristina Enescu

We all know and often make use of the therapeutic powers of music. Among the many forms of classical music, Baroque music seems to be particularly fascinating for audiences nowadays. The Enescu Festival 2019 had among its guests one musician who has dedicated many years to this flamboyant music, that takes its name from barroco, the Italian name given to `coarse and uneven pearls”. Italian conductor Ruben Jais and the laBarocca instrumental ensemble (whose creator, director and conductor he is) performed at the Festival an early composition of one of Baroque’s greatest composers, Händel. It was “Aci, Galatea e Polifemo”, a dramatic cantata based on the famous mythological story of the love between the mortal Aci and the sea-nymph Galatea, which gets a dramatic twist with Sicilian cyclops Polifemo falling for her and killing Aci.

With an obvious and infectious passion for Baroque music both on and off stage, Ruben Jais is a musician who happens to have also trained as a doctor, and at one point chose between the two careers. Which makes perfect sense, come think of it. Don’t doctors and musician, with different tools, seek to soothe and comfort people? Hence, at the Enescu Festival Ruben Jais seemed just the right person to talk about the fascination, beauty and soul-healing properties of Baroque music. Which, in its time, was labelled as dissonant, unnatural and weird, yet continues to be enchanting even to our XXI century ears.

Did you know that, according to medical studies, Baroque music has been shown to support and stimulate the brain’s learning and focus efficiency? This seems to be due at least in part to its mathematical structure (mainly repetitive forms), which makes the retention of information much easier by the human brain. Even more so, Baroque music has been shown to change brain waves and also influence the body’s physiology, researchers reporting interesting effects like improved pain tolerance and deep sleep quality.

What fascinates you about Händel’s dramatic cantata that you performed with laBarocca in Bucharest?

It’s a really beautiful piece, one of his early works (1708). It’s very interesting, at a lot of the brilliant material in this was later used by Händel in other operas, so from early on he was so rich in ideas. In 1718 he composed the opera “Aci e Galatea”, but the only common thing with this cantata is the subject, everything else is different. The most amazing of these three characters is Polifemo, and the extension of his part is quite wide. It is an astonishing writing for a bass, the harmonic changes here are breathtaking, the recitatives are so intense and demanding for soloists and orchestra alike.

What is it with Baroque music that is still so fascinating?

The beauty of Baroque music is based on its very clear structure, on the so-called “word painting”, which meant using the melody in a certain relationship with the meaning of the words sung. So, even for somebody who is not knowledgeable about music, this structure clarifies immediately the meaning of the composition. It paints with music the meaning of the words. The power of this approach is incredible, because the brain immediately recognizes the message. Baroque composers were people deeply rooted in the civilisation of their times, who felt they had to talk to their contemporary listeners, so they needed to be very clear in the way they communicated through their music.

On the other hand, it’s also a matter of music perception evolving through time. In 1724 when Bach composed St. John Passion, it was highly criticized. People were outraged, they said that was opera music, not sacred music. They weren’t used to such power in religious music. But somehow, from Bach on, that became the new road in music.

Baroque music being perceived at its time as scandalous is somehow understandable. Beethoven, Brahms and others were also not well understood by their contemporary listeners. You know, we had to wait until Leonard Bernstein’s performances of Mahler after his death to have his music revived. Composers are minds ahead of their times as they have to keep looking for new ideas, and often listeners are rather conservative.

Take Händel: he was not only a genius, but also a musician who understood extremely well what people liked, wanted and needed. When he arrived in London in 1711, he had this huge success with Rinaldo, so for about 20 years he composed only opera in Italian. Then, all of a sudden, nationalists said “why opera in Italian, it should be in English”. Händel was very clever: for him, opera had to be in Italian and it didn’t feel natural to switch to English, so he completely changed and started to compose oratoriums – in English.

Somehow, the needs of those times when Baroque music flourished seem to correspond to some needs nowadays, judging by the appeal that Baroque music still has today.

Absolutely. That’s because it is so direct, you immediately get it. I confess In Baroque, even when you have tragedies (like in “Aci, Galatea and Polifemo”, where everybody dies out of love, in the end), they happen in a very inspiring way, with a certain sense of hope and light. Maybe in very confused times, like ours are, this feeling in Baroque music is like the silver lining of a cloud.

Before being passionate about this, years ago you made a choice between medicine and music. How did that happen?

It was a weird situation, as a medical student I was working in a hospital in Milan in the surgery department, and one day suddenly I found my piano teacher as a patient there. I loved him, he had taught me so much. Three days later he died, and for me that was somehow a sign that I couldn’t abandon music. I decided that my way was to share the passion and beauty of music and its healing power.

Years later after that choice, how do you define success as a musician?

It’s when I manage to share my ideas with people, when I can create a feeling of togetherness through music. There are moments during a concert when you understand clearly that we all have a lot in common. You can recognize those moments by the complete silence in the music hall. The human bond created by music is simply amazing.

Image source: www.bach-cantatas.com/Bio/RubenJais