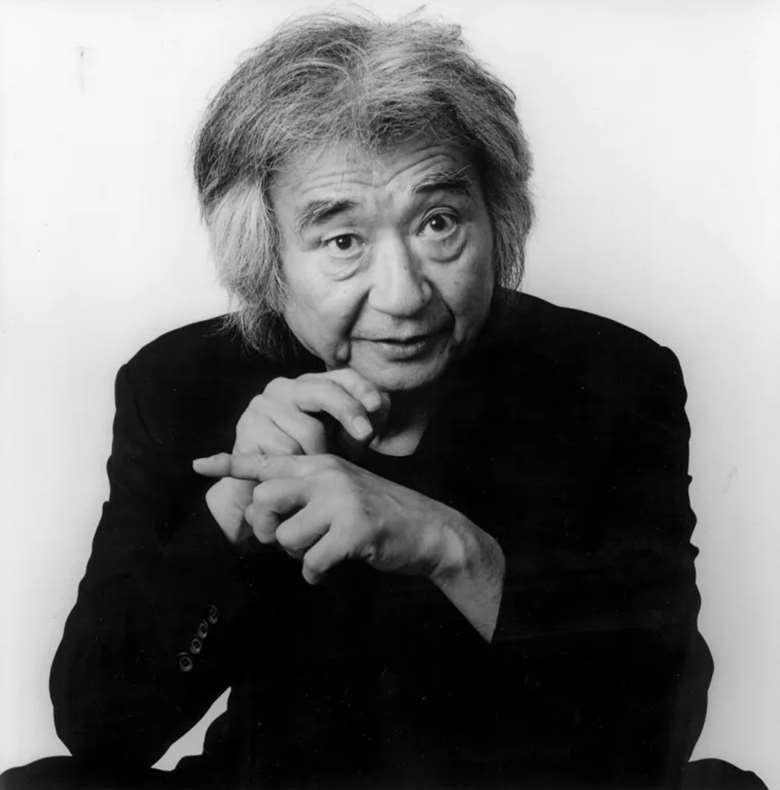

I met with Vladimir Jurowski on Wednesday evening, shortly after the concert in which he conducted the Berlin Radio Orchestra with a program dedicated entirely to Igor Stravinsky, wherein three of his works (The Flood, Renard, and Les Noces) received their Romanian premiere. The concert event was the (magical!) result of an ambitious project, with multimedia performance, four pianos, choir, soloists, and a narrator played by none other than the famous Robert Powell. After the concert, a small crowd of friends and fans was waiting outside the booth for their moment with the maestro. Once again, I admired and appreciated the generosity of a great artist who despite almost obvious fatigue agreed to give this interview. What’s more, he did so while smiling encouragingly.

Interview by Ruxandra Predescu

We are in the middle of the Festival, the hall was full tonight too. Nonetheless, how do we get more people into classical music, as there is not much concern for musical culture in schools? Certainly, a few notes from The Marriage of Figaro in a textbook can’t do much to make you fall in love with Stravinsky’s music, for example.

Stravinsky said, “My music is best understood by children and animals.” I think he is the ideal composer to attract children and young people to concert halls and we should somehow make them hear this music as early in their lives as possible, ideally even before they go to school. Like we do in Berlin, I think that every cultural institution of a certain status should design educational programs to popularize classical music, starting at early ages. We go to kindergartens, schools, hospitals, even prisons, and we work with people there; we bring them our music, but we also encourage them to play with us. I think active participation in this process is very, very important. Especially if we are talking about children, they have to be involved because that is the only way they will want to repeat the experience. If you just have them listen, sit still, and be quiet… that’s totally against their nature. And yes, education begins in school, but in this domain it actually must start much earlier, in the family. You know, if a pregnant woman listens to music, the baby is already influenced by that style of music. I would trust the sense and instinct of children exposed to classical music. And it’s very important not to intellectualize this experience of theirs.

What about adults who never had the chance to be exposed to this kind of music before?

In this case some fear is already there, but I think if we take the first steps towards them, if we bring the music to them, this audience will come to the concert hall later on. We’ve been doing this for many years. It started in England, but there are projects like this in Germany as well. It’s nothing new, it just needs to be done by people who believe in it.

What were your first thoughts when you were asked to take over the artistic direction of the Festival, what did you set out to do then and how has this changed, if at all, over the six years?

First of all, I wasn’t really sure I would accept this invitation, because I didn’t really have the time and space in my life for another major festival. I said then that I loved Enescu’s music and I would do my best to promote it, and Mihai Contantinescu [Executive Director of the Festival, Ed.] assured me that it was enough and that what he needed were my ideas; so I said “Ok, let’s exchange ideas.” In that sense, I can say that we managed to accomplish a lot, even though we worked mostly over email or phone calls and with my participation in the festival [concerts], of course.

The mission – although I don’t like the word – that we took on was to develop and promote the music of the 21st century, to bring new works to the Festival, like with the program just presented by the Berlin Radio Orchestra, operas, and I really think we managed to do a lot in that respect. Not just from my side, of course, but alongside the numerous artists who have been present at the Festival over the years. We also wanted to attract artists who would in turn become promoters of new music, artists that people would listen to and follow, such as Patricia Kopatchinskaja for example. I would say that we have pretty much achieved what we set out to do at the beginning of this journey. Of course, if I had had more time, we could probably have done even more.

What do you think the Enescu Festival needs going forward?

I think what it most needs is a concert hall. It has been promised to us by so many ministers of culture, I have seen three or four who have come and gone; they all made this promise, which remains unfulfilled to this day.

What do you think it takes for a conductor to be truly outstanding?

The ability to hear what you want to get and get what you want to hear.

If you could choose any composer and any work ever written to conduct its premiere, which composer and work would you choose?

I don’t know, it’s really hard to choose. If I chose just one, everybody else would be upset! I would have loved to see Mozart conduct the premiere of Don Giovanni. I’ve given a few premieres in my life and I was happy to have been given the opportunity, but I don’t think I would have liked to be the first conductor of Don Giovanni, for example. I’d rather be able to sit down for a beer or a cup of tea with a composer, but not necessarily conduct an opera of theirs in their presence, for the first time.