The first recital at the Enescu Competition 2018 brought on the stage of the Bucharest

Athenaeum two exceptional, charming British musicians, sharing a 36 years successful

partnership.

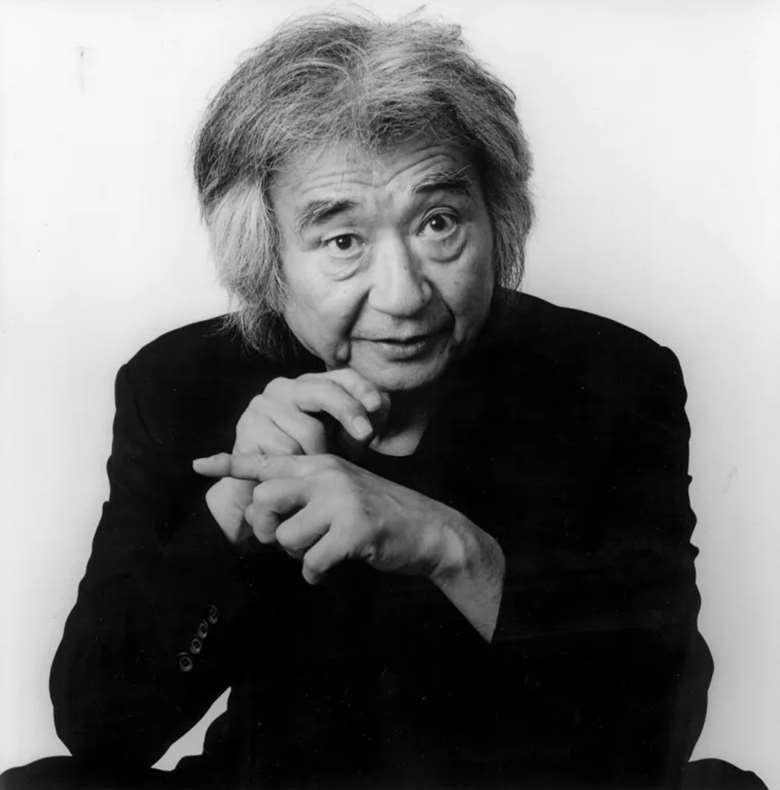

One of them, the renowned cellist Raphael Wallfisch was present in Bucharest as a member of

the specialized jury of the Cello Section of the Enescu Competition 2018, and also performed an

extraordinary recital as part of the programme of the competition, alongside pianist John York.

Cellist Raphael Wallfisch displays a mix of powerful technique and compelling musicality,

while his presence on and off-stage is both aristocratic and warm-hearted.

The latter was born to famous musician parents – pianist Peter Wallfisch and his wife, Polish

born cellist Anita Lasker-Wallfisch -, who is one of the most respected cellists around the world

and arguably among the ones with the highest number of recordings. Besides tackling a vast

repertoire, Raphael Wallfisch has had a keen interest in rediscovering and presenting forgotten

British and Jewish composers of the 20th century. After very young Raphael displayed an

attraction for this instrument, it wasn’t his mother who taught him. Instead, she guided him

towards some of the best teachers available.

Cello is his life. Literally. He would not have been here, had his mother’s life not been saved by

this instrument. Not once, but actually three times: twice in Nazi concentration camps, and then,

it was her music that helped her make a living. “My mother wrote a book about all that, ‘Inherit

the Truth: A Memoir of Survival and the Holocaust’. Cello was what saved her in Auschwitz

and then even more so at Bergen-Belsen. With 20 she was liberated, took up the cello again –

and that was her profession until a few years ago, when she stopped playing and devoted her

time to educating young people about the cello. Even more so, my son is a cellist too”, he says.

How did his own love story with the cello unfold? “Both my parents gave me the opportunity to

try out various instruments, without forcing me towards any in particular. Bu the cello… I did

quite like it from early on, I was 8 years old, but it was very important that I also had great

teachers. So, by the time I was 12, I was even more passionate about it.”

After decades of high-level concerts, numerous prestigious collaborations, recordings, concerts

and participation in competition juries, Raphael Wallfisch is very much still thrilled and

energized by this instrument. “It has become an extension of myself. Of course, my career has

involved a lot of hard work, especially as one chooses to play on a very high level. It’s a very

competitive profession. But I am very blessed with passion too, that’s my special ingredient. I

had a fortunate upbringing, surrounded by music, including with family friends around, like

composer Kenneth Leigthon, who stayed in our house when I was little and then later wrote

music for me.”

Kenneth Leighton is one of the composers who Wallfisch and York chose for their Bucharest

Athenaeum recital. All four pieces presented were somehow personally and emotionally

connected toWallfisch: Leighton’s Alleluia Pascha Nostrum was written for Wallfisch;

Austrian composer Alexander Zemlinsky’s late-Romantic Sonata in A minor for cello and

piano was lost for about a century until Wallfisch rediscovered it among his father’s papers;

famed Scottish composer Sir James MacMillan’s Sonata No 1 for cello and piano (which was

not only dedicated to Wallfisch, but also premiered by him and John York in 1999); and end of

the 19th century Belgian composer Guillaume Lekeu’s sonata (arranged for cello and piano by

Wallfisch based on some Ronchini notes).

“The first piece we played was written for me by Leighton in the 1980s. I had already played

several other pieces of his, as he was a family friend. I asked him to write a new piece and he

was very happy about it. He wrote this wonderful one, which I’ve played many times since.

Then again, he was the teacher of James MacMillan, so it was kind of natural that I then

gravitated towards MacMillan’s music as well – I played his sonata from tonight’s recital

many times around the world, even with McMillan conducting. So yes, there was that personal

connection with both composers, it all was quite natural.

With the Zemlinsky’s Sonata it was an extraordinary happening. An illegible copy was sent to

my father, a manuscript. We tried to play it, my father and I, but it was impossible because we

couldn’t read the harmony. So we left it. Many years later, after my father died, I was looking

through his music and I found it again. I though this must be a very important piece, as

Zemlinsky became a very well-known composer in the last 30-40 years. I sent the manuscript

to a musicologist who knows his style, and so it was rediscovered.

Then, the Lekeu Sonata… I had heard my father play the piece for violin, and I loved it. I was

thinking of making my own version for the cello, but then I found a very antique printed copy

of Ronchini, to which I made some small changes. Basically, I am the only cellist I know,

anywhere, who plays this piece. But I hope more people will start to play it.”

The “musical detective” work of Wallfisch is in fact more comprehensive. He is involved in a

project regarding five CDs with 20th century Jewish composers’ music, whose works have fallen

out of the spotlight mostly due to the historical context. This November he will be working on

the latest CD of this series, of which two are already out and two are on their way to the public.

Commenting on his research efforts, Wallfisch says “it really is the job of instrumentalists, to be

a voice for composers. That’s what we are. Of course, we all love to play famous composers

which everybody knows, it is always an honour. But there is much more than that, and there is

never actually enough time to play everything. I mean, for instance, my jury colleague, David

Geringas, has done huge work with rediscovering Russian and Lithuanian composers. There

is more music in the world that one can play. Our own repertoire, for the cello, is very big!

Many pieces were written and then abandoned, which is sad.

Many of the Jewish composers included in these five CDs knew my parents or my teacher or

were somehow connected to them. It’s a wonderful opportunity that I had, to champion these pieces. The fact that there is a disk out there means people will start listening that music,

maybe others will say ‘yeah, I want to play that too’, and then that music will be alive again.

I have been doing this research work also for a practical reason. Frankly, people are

interested to hear if you have some new, special music to present. If you play a Dvorak

concerto it’s wonderful and an honour, and I do it often, but I’m also very keen to play 60

other pieces, if possible. “

As for the place of the Enescu Competition among the most acclaimed international musical

competitions, Wallfisch sees the prestige of it in the wider picture of passing on the legacy of

classical music. “This Competition truly has a great reputation; many young people want to

take part in it. It is extraordinary we can remember George Enescu through this competition.

Enescu is such an aristocratic name in the history of music. He was this incredible musician

that we all admire, and it’s a wonderful thing to be reminded of his legacy through this

Competition. Lory Wallfisch, a distant relative of mine (and a famed pianist, harpsichordist

and musical educator born in Ploiești, Romania, later living in the U.S) was one of the

champions of playing Enescu, in America and all over the world. My own job here as a

member of the jury is to be as impartial as possible. It’s very hard, the level is truly high and

there are many deserving musicians. But you also learn a lot in such circumstances, and the

jury colleagues are so nice. The cello is a very collegial instrument; we cellists tend to like to

be together!

Classical music is a thing that we pass on, from generation to generation, and its traditions

are very important to be known. Musical fashion changes quite a lot in time, and sometimes

not for the better, so it’s good to know that which has been truly special throughout the history

of music – and Enescu was one of the very special people. “

About the impression his interpretations make on the audience, beyond a sense of obvious high

mastery, calmness and confident joy, he ponders: “I think we musicians are storytellers. Music

includes so many emotions, and that’s what I try to do, to get inside the composer’s head and

understand. That’s why it’s so hard to play, for instance, Beethoven or Bach, but even when I

play such composers from long ago, there is a story to tell.”