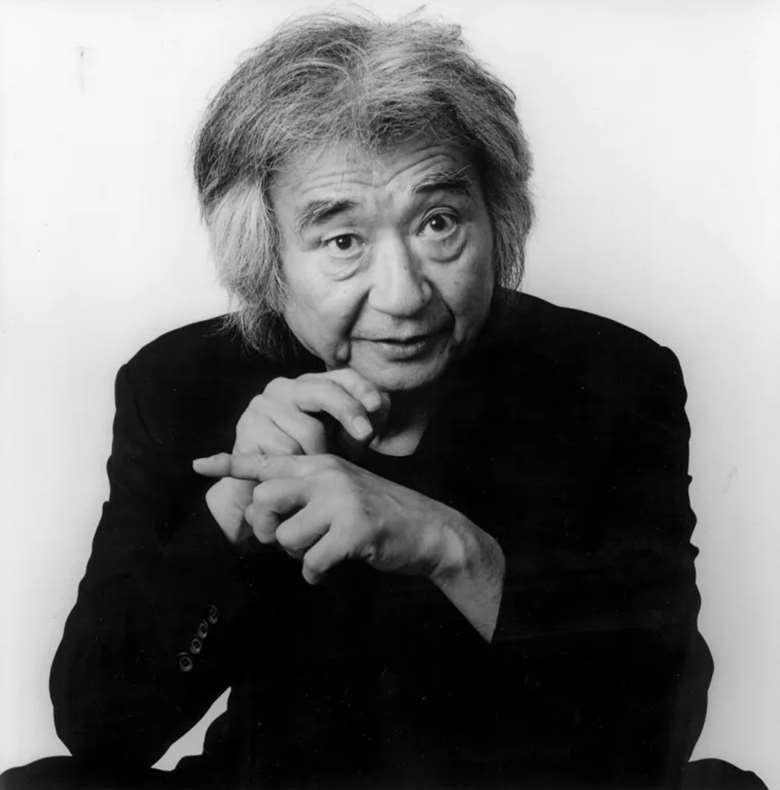

“Widely acclaimed” is an idea often coming up in reviews about him. The Milanese Daniele Gatti, whose baton has lead two of the closing concerts of the International George Enescu Festival 2017, has increasingly become one of the most significant concert and opera conductors of our times. He has also held important positions at iconic musical institutions, among which Teatro Comunale in Bologna, The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Orchestre National de France, Zurich Opera, Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome.

Interview by Cristina Enescu

”The most teutonic of Italian conductors” (as his country’s media recently characterized him) is known for his focused, highly professional, at times wayward approach to music, but also for the passion and vivid nuances he brings. Able to create a stream of fluid communication with the musicians, he is himself a musical spectacle worth watching during concerts. Whether through dramatic, powerful moves or almost immobile, silent ones, he certainly is an intense musician.

“Speak, speak!” or “Is it possible to play like the

Inhaling music and conducting magic

In Mahler he likes “to find the theatre”, Verdi’s Falstaff is “an incredible miracle” to him, Wagner’s music “is somehow like a drug, it captures you. Gatti approaches German, Russian, French or Italian composers with the same skilled approach, somehow finding the right blend between being faithful to the score and manifesting his own temperament. During the two last evenings of the George Enescu International Festival 2017, Gatti enchanted through the music of Mahler and Haydn (alongside soprano Chen Reiss), the Weber, Enescu and Prokofiev (featuring Concertgebouw’s concertmaster, Romanian violinist Liviu Prunaru). Several times he managed to create long, vibrating silence moments between the last note and the outburst of applauses.

Few moments before the last evening’s concert, while the backstage of Sala Palatului Hall was a beehive, maestro Gatti opened the door of his dressing room with the coolness of an admiral keeping his cool demeanor on agitated waters, as he knows well how to lead it to victory. An interview 7mins 55 secs long, and a lasting impression of musical and professional lordship.

Announcing you as the new chief conductor of the Royal Concertgebouw, the New York Times described you as “a creative risk-taker”. Others say you are not a traditional musician. What kind of conductor do you feel you are?

(He laughs) I hope to be a good conductor. I’ll try to answer like this: when I was a boy, studying music, (I began with piano at 12 years old), my teacher said: “Next time, when you return with your lesson, you have to say something about the music”. I went home and tried to read the music in front of me, to understand it and then to explain my feelings. This marked my life. Of course, growing in the study (piano, then 10 years of study of composition), I also got a lot of tools to analyze music. It’s not just how you feel the music. The world is full of people that have musicality. The difference between amateur and professional is that professionals are able to “rebuild” a piece, because you know how the piece is technically written. I think that, to be a performer, every time you open a score, even if it’s a Beethoven one, it should be like if the composer gave it to me, personally, one month before, saying “please, maestro Gatti, can you play this new piece?”. For me it’s important to have the closest relationship with the score. And if the score says to me that this tempo could be good, or the other one – not, of course, to be eclectic or odd, but to have my personality, I try to understand a piece of music and to offer it to the audience. Maybe two years later it will be different, but it’s different because I have also changed as a person, and the experiences that I have in my life are strongly influencing what I’m doing.

I come more to divide audiences rather than unify. I outline it strongly, it’s not a question of ecclectismo or, you know, eccentrism, it’s a question of how I understand a piece of music. And maybe I’m not a comfortable conductor for some. I think I’m a conductor that could create problems for some.

On the other hand, I believe I’m a musician that can be highly beloved because, if people want to listen to a familiar piece, revisited, I can probably fill up their taste. It’s, in a way, like seeing a picture – if you see a picture of the Colosseum, you recognize it. But I want to show you a picture of the Colosseum in the night, with a particular light. And you discover some angle or some other aspect that you never recognized before, because there was the common picture, under the sun, of that monument. We can try to penetrate a score in the maximum depth, the inner significance of the music. Sometimes I try also to read the music with another tempo or another articulation because, after analysis and also adding my vision and feelings to it, that is what I want to offer to the audience.

How can you manage to be creative and at the same time be “in the head of the composer”, like you said before?

Because the composer is just giving us some markings, the rest is an enigma for everybody. The difference between an actor and a musician is that the actor is talking and you can understand, a verb is a verb, an adjective is an adjective. If I say “to be or not to be” like this, or like that, I make an interpretation of those common words that everybody is able to understand, but inside the feeling is different from one interpretation to the other. In music, it’s the same.

I am in a search for the truth, and one life is not enough for that. My goal is to get as close as possible to that. But I tell you one thing, probably it’s quite strong what I say: even a conductor can arrive to the truth through one musical piece. Take Bruckner, he changed the same symphony three or four times, he wasn’t satisfied. He wrote it, then a few months later it was re-orchestrated, cuts were made… Music is in progress, it’s not like a dress, when it’s finished, it’s finished. Music is all the time in movement. For me, this is the search for the truth.

What makes Royal Concertgebouw one of the world’s greatest orchestras?

I think it’s the human beings, there are fantastic people there, and they are great musicians too, of course. The selection is very tight to get in there. And everybody points at the same aim, which is the highest quality possible.

What music are you currently seduced by?

The composer that I work with on a certain week. Now I’m fiancée with Prokofiev. Next week, when I’ll go with the Berlin Philharmoniker, my fiancées will be Brahms and Hindemith.