There is something unpredictable during the first minutes of a concert. A quiver of adaptation, sometimes of expectations, too. Sometimes the connection occurs instantly, sometimes it takes a little time for the music to grow from the inside, in which case my advice for music lovers is not to panic: it is hard to take off the clothes of reality and to enter a truly special Universe.

Text by Sabina Ulubeanu, composer

This is what happened when Daniil Trifonov played the first notes of Rachmaninoff’s Concerto no. 2. Nothing of his frail appearance predicted what followed on the evening of 9 September 2017 in the Grand Palace Hall, and the surprise was stunning.

Trifonov is a pianist with an overwhelming inner force, which is why choosing a slightly slower tempo in the first part of the concerto is no accident. It forces you to make an effort to concentrate, even though your mind is scattered. The chords at the beginning of part one, played in a deep, sober, interiorised manner, encapsulate all the weight of a long-forgotten world, a world where you had the time to feel everything fully, from the legendary three-year depression until the choice of a late Romanticism that Rachmaninoff was faithful to, because nothing is more important to a composer than the courage of their own voice, be it avant‑garde or retro.

Trifonov is a serious pianist at the same time. He affords himself no exaggerated sweetening of famous themes, his virtuosity submits to the musical meaning. He dominates sensibly in strong tones and manages almost unbearable colours in pianissimo. An example: the cadence of the second part sounded almost impressionist; as if I have never been as aware of the pedal pressed on the last phrase of the fragment that closes the beat, a fragment where the pianist gave himself some time.

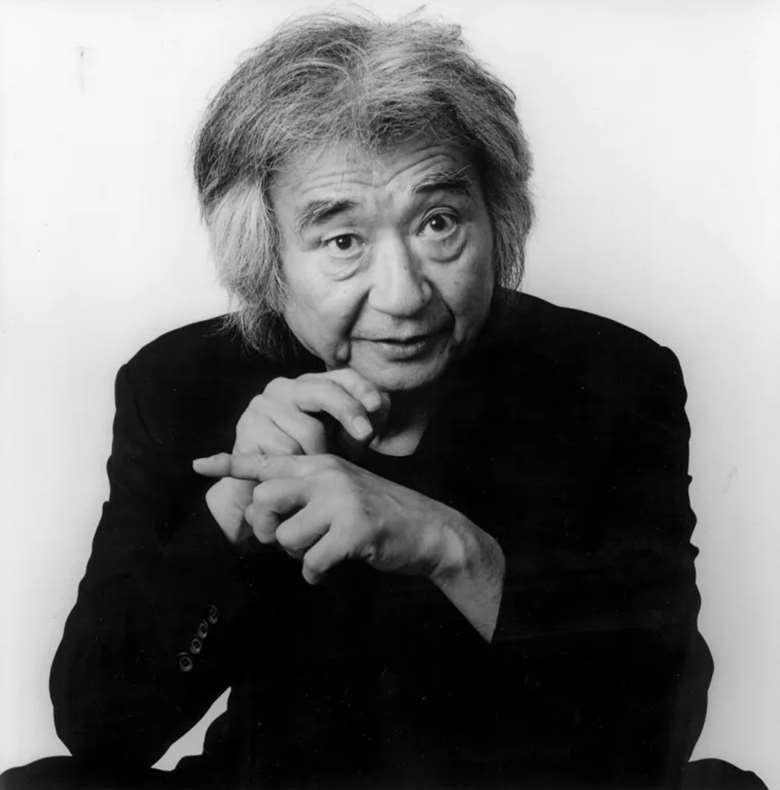

This is where the reviewer takes the opportunity to introduce the evening’s hero in action. Trifonov gave himself time, and Valery Gergiev turned this time into one of the most complex and enveloping orchestral expositions. It was no accompaniment, it was a dialogue, a feverish emulation of the soloist’s moods, a subtle pursuit of the mad race in the third part, a timbral exacerbation of ideas – we cannot forget the resonance of the double basses, with the instruments placed on the left, near the first violin section, so that the fugato in the third part sounded almost like a spectral music.

Just 26 years old, Daniil Trifonov is not far from the age when Rachmaninoff wrote this concerto, and even though today youth is synonymous with casualness, his performance did indeed break the mould, integrating so well the whole depth of this music into his vision, generous and personal alike.

Long applauded, he returned on stage, and his encore revealed an impetuous Chopin’s Fantasie-Impromptu, once again on the verge of unbearableness in the intensity of median pianissimos. An almost painful moment, when some of the audience started whispering in some sort of moan, a moment that reminded me of the legendary story of Sviatoslav Richter, in the early 60s, when the public of Bucharest had an identical reaction during Beethoven’s Appassionata.

The second half of the concert brought together three legends: Anton Bruckner’s Symphony no. 4, the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra – the epitome of tradition, shaped in the sound of Bruckner – and the conductor Valery Gergiev. I don’t think I have ever listened to this symphony with more patience. It is easy to close your eyes and let yourself carried away by the spatial and temporal expanse of Bruckner’s harmonies, orchestrated in such a complex, yet effective manner, so convincingly that you may think no other version could ever be possible in the history of music.

Now I have focused on the way that fifths turn into octaves, octaves into ascending and descending scales, with no bias regarding the use of simple, precise techniques: a model with two sequences, taking the last two notes of a motif and building an entire section using only these, melodies turning into choral elements, an ironic slap on all the jokes about viola players – all you need to do is listen to the theme in the second part to forget them all –, a stunning lightness of the themes exposed for the strings, because Bruckner does not have a lot of humour, but plenty of lightness, and even this is uplifting, and above all, the Unison, that supreme Unison, the explosion in the fourth part, which takes you so beautifully into the reality of the composer’s life: the organist that made a living in Sankt Florian, gave a concert in Bayreuth in a rather small church, just to visit Wagner, and who then put the organ in the orchestra: a single sound, 100 instruments as a single one, and colours seemingly moulded on the modern physiology of breathing and mindfulness lessons.

And above all, Gergiev.

With an almost frightening precision of emotion, yet with wide breaths, with his delicious manner of revealing every compartment of the orchestra and with the pleasure of unearthing details, over which hovered all the influences of the music before and after this symphony, triggering a formidable response of the Munich Philharmonic to every one of his gestures.

In the end, I had the feeling that the seriousness of the first chords played by the very young Trifonov and the time he gave himself sublimated in this symphony written by Bruckner, a music I wished would never end.

And how great that, in fact, music is time and it never ends…

Translation provided by Irina-Marina Borțoi, Biroul de Traduceri Champollion