At the Enescu Festival, 9 September 2019 was a day of interiority revealing itself with gentleness, refinement and passion. It started with the concert at the Athenaeum, where pianist Plamena Mangova and cellist Alexander Kniazev simply electrified the audience. Enescu’s Sonata no. 1 in F minor is a composition written in his youth, despite being numbered opus 26. Written in 1898, a study composition where you can hear influences from the second part of the recital (Brahms and above all, Franck), the sonata is monumental, physically demanding for the artists, as the wide breath of the sections simply cannot be fragmented. Kniazev has the gift, in any composition, to transfigure moments of quiet, giving them an almost extreme tension without using anything emphatic, nothing too much or too obvious, contorting the tension in enchanting areas of the subtle that one doesn’t even imagine possible. Plamena Mangova seconded him with composure and delicacy, leaving us to discover her better in the second part of the recital. Because in Brahms’s Cello Sonata no. 2 (in F major op. 99) and in the cello version of César Franck’s sonata, the qualities of this remarkable pianist shone bright. Without mellowing anything of the romantic discourse of these works, the two protagonists carried the audience to a place of authentic warmth, pure communication between two musicians that make chamber music together, so that, for me, it was the most intimate and generous recital in the festival so far.

Staatskapelle Dresden followed at the Palace Hall, with Myung-Whun Chung at the helm, a famous conductor in the music lovers’ world for his fabulous performances of French music, particularly that of Olivier Messiaen, his version of the Turangalîla-Symphonie being iconic. The programme was German, stopping by Enescu halfway through. Weber’s “Der Freischütz” Overture, Enescu’s Sept Chansons de Clément Marot, and in the end, Johannes Brahms’s Symphony no. 4 in E minor.

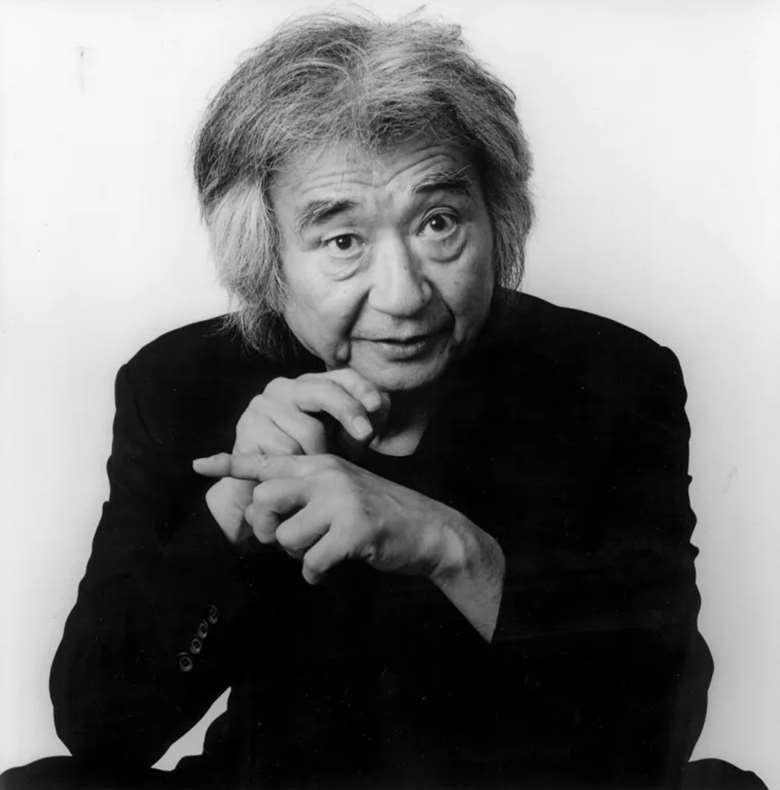

Although the Freischütz premiere was held in Berlin, Weber’s connection to Dresden is profound, as he managed the opera starting with 1817, as one of those who strongly believed in German music and its power of expression, including in opera. It was precisely this visionary side, directed towards the future of music, that I felt in Myung-Whun Chung’s performance. The Korean conductor is that type of personality that you either love or reject. For me, it is the first option particularly due to his extreme finesse, his inner power of leading the orchestra just with his gaze, with contained, minimal gestures, with that hand held above the heart that brings out the best in artists when it comes to the lyrical. It was a mysterious overture, dark at times, of planar dramatism.

In Sept Chansons de Clément Marot, soprano Laura Aikin brought back, along with the orchestra, the charm of a Paris that our grandparents’ generation used to adore, and Myung-Whun Chung understood the fantastic specificity of Enescu’s orchestration: vivid colours, elegant withdrawals, suspended time connecting to the great arch of the cycle of lieder. Laura Aikin’s voice sounded in perfect harmony with the orchestra, she may have lacked some brisker nuances, but the way the instruments took over every line, motif and musical idea made the performance of these pieces a source of delight.

Entire books are still being written about Brahms’s Symphony no. 4 and symposiums of comparative performance are still debating the best way to bring this fabulous music to the public. “As a musician, being a conductor is the worse, as you don’t produce any sounds” said Myung-Whun Chung modestly in an interview. He also says it as an exceptional pianist, winner of the Tchaikovsky Composition in 1974, but with his extreme finesse, together with the Staatskapelle Dresden, miraculous sounds were produced. The Korean conductor has an almost mystical view of music, which was fully apparent on the evening of 9 September at the Palace Hall. The main theme in the first part, a very organic one, was rendered with intimate warmth, without emphasis or exaggeration (for connoisseurs, a descending third, reversed into a sixth, followed by the expansion of an octave and then by another third, ascending this time, perhaps the most economical manner of working with intervals in profound romanticism and thus generating a part of the composition). I have never heard such an expressive dialogue between the timpani and the triangle in the third part, a triangle that almost seemed like a glockenspiel, of an otherworldly shine. I witnessed such a refined Brahms that it seemed like all the sounds of the 21st century had blended in his conducting vision, mainly in the final chaconne. It only showed grandeur in well justified moments, which left some senior music lovers a little puzzled and discontent. But sometimes it’s good to be challenged by a new performance and to overcome the barrier of the familiar, so as to find other valences of the score. After all, everything that Myung‑Whun Chung did had already been written by Brahms, all he had to do was translate it in this refined, sublimated manner that carries one to the profound depths of one’s being and gives one pause.

Sabina Ulubeanu, composer

Translation provided by Biroul de Traduceri Champollion